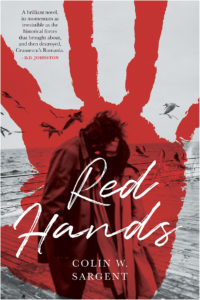

Red Hands

The Untold Story: The Dictator’s Daughter-in-Law

Iordana Ceausescu of Romania

Selected as an Amazon Kindle Book of the Month, May 2024

Talk Radio Europe Interview, Malaga, Spain

KIRKUS REVIEWS

Poignant, frightening, packed with historical nuggets—a cautionary tale for contemporary times.

Sargent’s novel is based upon the life of Iordana (Dana) Borila Ceausescu, daughter-in-law of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. Written as a fictionalized memoir composed in the voice of Dana Ceausescu, this narrative is based upon Sargent’s interviews with the beleaguered ex-wife of Valentin Ceausescu, scion of the family that ruled Romania from the late 1960s through the 1980s. The interviews took place in Maine, where Dana and her son, Dani, lived in hiding after Ceausescu was overthrown and executed in the violent revolution of 1989.

Born and raised in Bucharest, Dana is the daughter of devoted communists—her father is a high official in the Central Committee, and her mother is a respected newspaper journalist. As such, the teenager has enjoyed a life of privilege. Her parents’ fortunes begin a dramatic decline when Nicolae Ceausescu seizes control of the Central Committee in 1965. In that same year, Dana meets and begins dating Nicolae’s son, Valentin Ceausescu, much to the displeasure of both families. The couple marries in 1970, and Dana acquires a mother-in-law, Elena, who despises her (“Elena, through her network of Central Committee wives, began a disinformation campaign filled with rumor and innuendo about me that flashed all over the city”). Meanwhile, Nicolae becomes a media darling during the early years of his reign, turning to the West for loans to finance his plans for industrializing Romania (much of this money finds its way into the Ceausescu private coffers). Eventually, crippling debt plunges the country into chaos.

Sargent’s novel is both a personal story of deep romantic love and a terrifying historical lesson about life in a police state helmed by a ruthless, cult-of-personality dictator. Always considered an outsider, Dana is nonetheless privy to the Ceausescu family’s extravagances and its unspeakable cruelty. Dozens of daily-life vignettes effectively capture Dana’s moments of joy and heartbreak, and the pervasive fear that extends as the scarcity of food, electricity, and heat grips the country. There’s even a breathless car chase across the border, with celebrity race car driver Catalin Tutunaru at the wheel.Poignant, frightening, packed with historical nuggets—a cautionary tale for contemporary times.

KIRKUS REVIEWS

Poignant, frightening, packed with historical nuggets—a cautionary tale for contemporary times.

From Maine Sunday Telegram

In ‘Red Hands,’ a close-up tale of life under Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. It’s not pretty

Ceausescu and his wife wrecked the lives of their countrymen – and their own family. For a spell, their daughter-in-law and grandson laid low in Old Orchard Beach.

Reviewed by William Barry

“If there were a secret Gulag hidden above New York, maybe it was Maine, thrust into the dark Atlantic Ocean like an angry fist. Not only was this northeastern most point of the United States a border state with Canada, but it was also the most obscure, its face turned into the wind.”

So writes Colin Sargent, Portland playwright, novelist and publisher, near the outset of his new true story “Red Hands.” His latest book begins with a bit of sleuthing on our own turf. Sargent has a knack for finding and expanding upon little-known historical nuggets; he’s previously written about Italian sub-mariners stationed in Portland late in World War II and about Portland-born Mildred Gillars, who became the radio propagandist for the Nazis known as “Axis Sally.”

Here his story follows a mysterious woman in Maine, so out of place he refers to her as “a black swallowtail in the snow.” The woman turns out to be Iordana Borila Ceausescu, daughter-in-law of the brutal Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu (1967-89). “Red Hands” gives a unique insider’s view of the rise and fall of the dystopian regime of Nicolae and his wife, Elena. It is also a love story of Iordana for the couple’s eldest son, Valentin, as told to Sargent by Iordana during her exile in Old Orchard Beach, where she hid for several years after the bloody 1989 revolution that toppled (and executed) her in-laws.

Told in a literary Truman Capote “In Cold Blood” fashion, “Red Hands” gives the reader a clear picture of privileged life in Romania, where the couple’s tense lives hovered somewhere between the communist East and the capitalist West. Her marriage to Valentin brought Iordana many privileges. At the same time, she lived a life of constant uncertainty because her powerful mother-in-law detested her.

The Romanian government led by the Ceausecus practiced repressive surveillance and thought control on its citizens, from the lowliest workers to the highest government officers. Nicolae and Elena ruled as harshly and effectively as any dictators of the 20th century, yet they were seen as liberal, even progressive by western governments. How this Potemkin Village façade was achieved is clearly spelled out in “Red Hands.”

Even trivial things are fraught. In one scene, Iordana travels to the countryside in a lavish but dusty official car on which someone had written “wash me. ” While Iordana is visiting friends, the terrified villagers wash the car. The fear across the land was palpable. Nobody dared to say anything that might upset the Ceausescus. I have always wondered how Hitler was able to come to power in an educated nation. Even though I studied the subject with a professor who had served in the Hitler Youth, I was still somewhat incredulous. But after reading “Red Hands,” I finally understood.

Both Nicolae and Elena began as committed communists who fought the fascists in Spain and the Balkans. They were true believers – part of the old guard that rose to rule Romania with Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej after World War II as part of the Eastern Bloc. But in their rise to the top, they became worse than their fascist and royalist predecessors. The joke was that everyone knew what was going on, but nobody dared to speak up.

Young people at the top, like Iordana, had access to western culture, films like Lawrence of Arabia and To Kill a Mockingbird, music like that of Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, but they were not allowed to travel, and they lived in the same atmosphere of terror as everybody else.

In Iordana’s case, her mother-in-law, especially, disapproved of her Western ways and found devious ways to punish her for them. Slowly, Iordana learns that her own parents, once trusted, high-level Communist party members, were being stripped of party privileges as a backhanded way to hurt her. She thinks she is being watched (the Secret Police in Ceausecu’s regime were infamous) or even poisoned. The terror comes from both sides: She receives strange and frightening telephone calls from anti-government individuals. When the police are able to identify the callers, they tell Iordana “not to take the calls seriously, we had no dissidents or criminals in Nicolae’s Romania, ‘only crazy people.’ ”

Eventually, life grows so pressured, her marriage falls apart. As the situation for her and her son Dani worsens, they escape Romania through Yugoslavia and then Israel before coming to the United States by way of Canada. Mother and son settled in Old Orchard Beach in the 1990s, where Dani eventually graduated from high school.

Writer Colin Sargent was introduced to Iordana by a Romania race-car driver whom he’d interviewed for a previous article. When Sargent showed her a version of his book, she asked that he delay publishing it while she lived. In 2006, he learned that she and Dani had returned to Bucharest, where she died in 2017.

The taut, vivid writing in “Red Hands” – there are no wasted words – makes for a fast-paced, heartfelt book for our time, when many Americans seem to have fallen under the spell of a man who spouts dangerous nonsense. The fate of the individual caught in distressing social and political times is sadly eternal.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History,” and is now at work on a history of the Maine Historical Society. He lives in Portland with his wife, Debra, and their cat, Nadine

INTERVIEW: Portland Press Herald, May 1, 2024

Local man of letters Colin Sargent reflects on one of the most important stories of his career. Sargent’s book “Red Hands” recounts the life Iordana Borila Ceausescu, the daughter-in-law of Romania’s infamous dictator.

Iordana Borila was in love. The year was 1965 in communist Romania. She had met dashing Valentin, one of her classmates and goalie on the school soccer team. The young lovers snuck around, hung out in the park. They kept in touch with calls and letters while he studied in London, and they eventually married.

There was only one problem, Valentin was the oldest son of the Romanian dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu – and their union forever linked Iordana Ceausescu to the excesses of the Ceausescu regime and the turmoil the country would undergo at the end of the 20th century. She would eventually flee Romania following the execution of Nicolai Ceausescu and his wife, Elena, during a bloody revolution in 1989. Valentin survived but would stay behind in Romania.

Kennebunk resident Colin Sargent, a writer and the founding editor and publisher of Portland Magazine, first met Iordana Ceausescu in the 1990s when she was living with her son in Old Orchard Beach, hiding out from the world.

Her life became the subject of his third book, a “nonfiction novel” called “Red Hands.” Even in death (she passed away in 2017, according to Sargent), she remains a source of inspiration and admiration for the author.

The two were introduced by a former Romanian race car driver that Sargent had met while writing a review. It quickly became clear to Sargent that he had stumbled on a story that needed to be told.

“She looked down, radiating a strange combination of shyness and privilege,” Sargent recounts of their first encounter in the prologue of the book. “It couldn’t be. Was this the daughter-in-law of the executed dictators of Romania? I took her coat and hung it in the hall closet. What on earth was she doing here? How had she found herself in Maine? A black swallowtail in the snow.”

Sargent conducted over 800 hours of interviews with Ceausescu that form the basis of “Red Hands,” which he agreed not to publish until she passed away. “Red Hands” was first released in the United Kingdom in 2020 and last year in the United States.

In “Red Hands,” Sargent presents the greed of the Ceausescu family coupled with Nicolae Ceausescu’s economic mismanagement of the country, which led to shortages of fuel, food and other necessities.

During an early visit to the “main palace,” Iordana Ceausescu recounts: “In a storage room built like a bunker, we saw stacks of leopard skins and tusks from Idi Amin; gold and silver presentation platters, pitchers, tea sets, loving cups; priceless marble statuary; Turkish and Persian carpets; Ottoman chalices encrusted with jewels; Chinese lacquered furniture and antique porcelain; crystal; Delft pottery; and paintings from all over the world.”

The extent of that wealth was revealed to the country during the revolution.

“She started unseeing herself as innocent and seeing that she was culpable for some of the things that happened,” said Sargent.

The book is told from Ceausescu’s first person perspective. When asked why he chose that format, Sargent said simply “because that’s how I became aware of (her story).”

While the book does recount historical episodes – like the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 – Sargent acknowledges that relying so heavily on one person’s narrative necessarily blends truth and fiction.

“When you have recollected conversations, and there were many of them (in the book) that were over 50 years old, it’s not responsible to say it’s fact,” he said.

During their many interviews, the two became close, said Sargent. Sargent described her as “elegant,” “intelligent,” and also a “significant romantic.”

It’s no wonder they got along. Sargent himself has a romantic streak – keen to see the beauty and poetry in everyday life.

Just take his observations about the ocean that came up during our interview: “I think a lot of people in Maine … a whole big emotional part of them is the ocean right beside their world,” he said. He said he sees the shore as latent with meaning: a liminal space that represents change and possibility.

“In early June, a bunch of high school seniors will start flocking to Gooch’s beach … because they’re teetering on the rest of their (lives) and it’s an enormous time for them,” he said. “That’s why there’s so much literature about people that age. They’re standing at the water’s edge, which is an objective correlative for the rest of their lives.”

Sargent grew up in Portland but spent his summers in Kennebunk. Today he lives in the same cottage he visited during those summers, a cottage nicknamed the Black Pearl. He got his start in writing while contributing to his high school’s newspaper. Later, he attended the Naval Academy in Maryland, where he studied English and wrote poetry. Then, while working at what was then called the Naval Safety Center in Virginia, he was an editor for Approach magazine, the “Navy and Marine Corps Aviation Safety Magazine,” which first launched in 1955.

He went on to get a Stonecoast MFA in creative writing from the University of Southern Maine and a PhD in creative writing from the University of Lancaster in the United Kingdom – eventually authoring three books of poetry and two novels before “Red Hands” – but he chose to highlight his time at Approach when asked about where he got his start as a writer.

“You had to assume that aviators in ready rooms and on carriers (had) a very low attention span except for what they’re doing,” he explained, meaning that he learned quickly that there was no room for boring stories in the magazine. “All of our stories began at 10,000 feet in icy altitudes with an impending crash,” he remembered.

From the experience, Sargent drew the conclusion that when it comes to storytelling, “people want a ride. They want to be excited.”

It’s fair to say he applied that approach to “Red Hands,” with success.

Readers have also awarded it largely positive reviews on the book reviewing site, Goodreads. It was recently chosen by Amazon Kindle as a “Book of the Month” in May, according to Sargent.

“My family and friends are so proud that I have been able to keep Iordana’s voice and point of view alive, which is so important in these times of rising nationalism,” Sargent wrote in a follow up email.

Sargent does not have any book talks or events scheduled, but he hopes to plan some for the summer.

He also said he has a new book coming out this year, “Flying Dark,” which he describes as a “horror romance” that draws on his experience in the Navy and his love for the coast of Maine.

On Amazon and Goodreads

Named one of the Top 6 Books in the UK by the London Morning Star!

“In Red Hands, author Colin Sargent employs a part-autobiographical, part-fictionalised first person account of the troubled life of Iordana Ceauscescu, wife of Valentin, the eldest child of Nicolae and Elena.

Fittingly, haz de necaz — the Romanian term for rueful laughter — appears a number of times in this novel and it pretty much describes Red Hands’s tone, one of tragedy leavened by comedy.

Sargent is at his most skilful and immersive in describing the interior life of Dana as she both seeks to accommodate Elena’s wishes while trying to retain the affections of Valentin.”

“Colin W. Sargent’s Red Hands is a thrilling true-life tale drawn from interviews with the Romanian dictator’s daughter-in-law Iordana Ceausescu.”–NB Magazine

Midwest Bookreview

Reviewed by Mari Carlson

Colin Sargent describes crafting Red Hands, his latest novel about Iordana Ceausescu, like salvaging scattered crystals from a shattered chandelier. For her, telling this past is not unlike shattering into a thousand shards all over again. Sargent’s depiction restores her as a luminescent and resilient whole set against a turbulent background.

Ceausescu grew up in Romania’s Nomenclature (communist party).

Both her parents had high positions in the government. As her father and his colleague Nicholas Ceausescu conflicted over Romania’s direction, Iordana’s infatuation with Valentin Ceausescu tempted her teenage rebellion. But the thrill of taking risks turned into fear after their clandestine marriage. The Ceausescu family disavowed her and she, in turn, rejected many of their lavish gifts. She kept Valentin’s baby despite the family’s disapproval. She and Valentin divorced amidst political unrest sweeping communist countries in the late 1980s. She and her son fled the country when the Ceausescus came under attack.

The dangers Ceausescu faces become all the more convincing in Sargent’s depictions of their interviews in which information leaks out bit by painstaking bit. In contrast, she comes across in the rest of the story as a confident and principled woman. The novel focuses on the actions she takes to protect herself, her son, and fellow citizens. “The people were free without Communism and the Ceausescus but they were desperate without someone to blame” (254). With elegance and journalistic precision, this novel speaks to the timeless struggle of individuals up against powerful collectives.

About the reviewer: Mari Carlson is a violinist and writer living in Eau Claire, WI. When not reading and reviewing, she is likely teaching or practicing violin. She is an active member of area chamber orchestras and folk ensembles.

Historical Novel Society

Review by Helen Johnson

Red Hands opens like a thriller, and keeps up the tension, even as the narrative voice of Iordana Borila describes a golden, happy childhood in 1960s communist Romania. Things begin to lose their sheen when she meets Valentin Ceausescu, son of her father’s political rival. Their marriage – opposed by both sets of parents – launches Iordana on a trajectory described as “if Juliet did not die”.

Sargent’s work reads like memoir, written in Iordana’s voice. But Sargent’s skilled writing provides vivid images, lively character studies, a portrait of a brutal, controlling regime, insights into the nature of love, friendship and courage, and tension maintained at such a pitch, that it was almost a relief when the blood eventually began to spill. In an era of books geared to gendered markets, there’s more than enough of both romance and political intrigue to satisfy both groups.

The cover blurb claims that the book is drawn from 800 hours of unique interviews with Iordana, a real person, who died in 2017. So why is Sargent’s book billed as a novel, and not a ghostwritten autobiography? In an interview with his publisher, Sargent explains “Novels are the highest form of truth”.

That’s as may be. But in an era of “fake news”, I’d have been grateful for an author’s note to clarify these points. Without it, I am left wondering whether the 1980s are too close for “historical” fiction. Nevertheless, a great read.

“Blood and Chaos: Iordana is a normal girl, brought up with all the perks of Romania’s corrupt communist regime. Then she falls in love and marries the eldest son of her parents’ arch-rival, Romania’s monstrous dictator Nicolae Ceausescu.”– Crime Time

Morning Star Review

Red Hands

by Colin Sargent

Barbican Press, £12.99

Haz de necaz. The term – Romanian for rueful laughter – fittingly appears a number of times in this novel. It pretty much describes Red Hands’ tone – tragedy hardened further by comedy.

After his extraordinary second novel, The Boston Castrato, Colin Sargent shifts his intelligent and sharp focus from the 1920s USA to the Romania of the 1960s onwards.

Employing a part-autobiographical, part-fictionalised first person account, he empathetically describes the troubled life of Iordana Ceauscescu, wife of Valentin, the eldest child of Nicolae and Elena.

Although increasingly critical of Romania under the wonderfully self-described Danube of Thought and the Mother of the Nation, this is less a comprehensive critique of the Romanian socialist regime than a very personal story of love and loss amidst senior political families.

Herself the daughter of senior communist party members, “Dana” has the temerity to exercise self-agency by marrying Valentin, the most self-contained and least ideological of the Ceauscescus.

Having done so in the face of opposition from both families, but especially against the express instructions of the ironclad Elena, the young couple are pretty much cast out of the Ceauscescu orbit, although not entirely free of the ministrations of the Securitate.

Sargent is at his most skilful and immersive in describing the interior life of Dana as she both seeks to accommodate  Elena’s wishes whilst trying to retain the affections of Valentin. The latter, as with all the Ceauscescu children, slowly succumbs to the immense gravitational pull of his parents, causing Dana further humiliation and heartbreak.

Elena’s wishes whilst trying to retain the affections of Valentin. The latter, as with all the Ceauscescu children, slowly succumbs to the immense gravitational pull of his parents, causing Dana further humiliation and heartbreak.

Her becoming pregnant, far from reconciling Nicolae and Elena to her, serves only to infuriate the older couple, proof for them that Dana is out of their control. Yet, thanks to a kindly doctor, her son is safely delivered, although the boy is largely ignored by his paternal grandparents.

The book then delves into two supreme ironies: the first purely personal and the second the personal consequences of the political. Firstly, Dana and Elena’s relationship starts to thaw – thanks to Valentin openly having an affair with another woman.

Then, Nicolae and Elena are toppled in the coup of December 1989 – and bearing the name Ceauscescu is a potential death sentence, the subject of much “Haz de necaz” on Dana’s part given her treatment by the family.

Although we know that she and her son survive, Sargent’s description of the street battles and looting in Bucharest are palpitatingly told, fully engaging the reader in the narrowness of their survival.

This is a fine book and an excellent read. But it doesn’t set out to be anything other than a partisan account from Dana’s perspective. Elena and to a lesser extent Nicolae, are reduced, if not to stereotypes, then at least to comedic and two-dimensional entities. The impact of their own hard upbringings and fighting the fascists as young communists, only occasionally peeks out from underneath their propagandised facades.

Paul Simon

Interview with Colin W. Sargent on Red Hands

Red Hands is a deeply compelling tale of a woman caught inside the destruction of a regime.

Iordana is a normal girl, brought up with all the perks of Romania’s corrupt communist regime. Then she falls in love and marries the eldest son of her parents’ arch-rival, Romania’s monstrous dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. They become the in-laws from hell, but she brings them their only grandson. And then there’s the 1989 revolution, when crowds will kill anyone with the Ceausescu name. In all the blood and chaos, can Iordana keep her little son alive?

‘An astonishing work, brilliantly told. In Iordana Ceausescu, Colin Sargent has given us a fascinating window into the brutal regime of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu and their near destruction of Romania. A cautionary tale for our times.’

—Nancy Schoenberger, author of The Fabulous Bouvier Sisters

Red Hands is a compelling read. You get pulled in to the story of a young girl’s life, and then find yourself led through the excesses and collapse of a whole Communist State. As the book’s editor, I know that such a vivid read only comes out of a tough and disciplined writing process. So once the novel was off to print I asked Colin these few questions.— Martin Goodman

Martin: Red Hands draws on eight hundred hours of interviews with Iordana Ceausescu. With so much detail, why did you choose to write the book as a novel?

Colin: Novels are the highest form of truth. Her story is a cautionary tale, and while it focuses on her personal experience of getting involved with a dictator’s family, it represents a whole country. Both history and her mother warn her about breaking the taboo. The more I listened to Iordana, the more I realized it was a horror story. If we’re not careful, we can all get seduced and then destroyed by the nightmare.

Martin: At what point did you decide you had to commit to the project?

Colin: The moment she asked me to listen, I realized she had no one to trust. Here we were, two strangers from completely different worlds, different social strata, different genders. The only experience we really shared was, we both had a son. She was willing to go out on a limb and share with me. I’m a writer. I really had no choice.

Martin: Were these strictly interviews, or more like conversations? Could you say something about their shape, and how you structured the time?

Colin: Anyone who knows me knows that all conversations are interviews. The whole time we talked, Iordana was hiding in Maine. Always involving coffee (“You need a teaspoon of sugar for the liver”), often involving dinner and wine. One time and one time only: miniature golf. There was one point where she and Dani found themselves homeless, so we welcomed them as guests.

Martin: How probing could you be? And how hard was it for Iordana to recall what are often very intimate and troubling details?

Colin: Iordana could play possum. I always had the feeling we were talking in twilight, certainly she negotiating and me stumbling around in the dark. Sometimes she’d be cunning, bright-eyed, and loquacious, but if I hit on a topic where she felt really vulnerable she’d suddenly curl up and play dead. If she did this I’d stop, but I’d make a note of it. I’d put a star in my notes. Then, I’d go back during another interview to see if she’d relaxed about this. Sometimes I’d wait as long as two years before I felt the time was right. It did take a continuous review of my own notes. Very slowly, patterns emerged.

Martin: What did you need to do to forge Iordana’s voice?

Colin: I captured Iordana’s voice without stealing it–which would have been another crime against her.

Martin: Did she recognize her own voice in your work?

Colin: I certainly hope she did. Of course, Iordana never wanted to see the final manuscript. She became afraid of the very idea of the project itself. Over time I shared parts of it with her. I especially liked it when she’d smile, look up, and say, “How could you know?” I don’t ever remember her saying this isn’t true, but I do remember her saying, “This is too true.”

Iordana Ceausescu

Martin: What were Iordana’s hopes for all these hours spent with you? What did she want the book to achieve?

Colin: When I first met her, she was desperately out of resources. She didn’t want this to happen again. She wanted deeply to be heard. She didn’t want to be dismissed and wind up one of the silent dead in the subway. But she was also concerned about Dani being caught up in a whirlwind he couldn’t control. Dani at eight had certainly seen himself on posters in the subway calling for his death as the “Dracu” grandson.

Martin: What were her reactions on reading the manuscript?

Colin: Enthralled mortification. Laughter. Deep embarrassment. Relief. Fear. Toward the end of our relationship, when I floated the title Red Hands, she looked me in the eyes and winced. “What must you really think of me?” She looked down at her hands. “They are.”

Martin: That’s pretty intense. How did she feel about others reading it?

Colin: If you were reading it right now, she’d shake her head, eyes down, and ‘shyly’ take it out of your hand. She’s revealed too much; you’ve come way too close. Who do you think you are, anyway, to see this? The next morning, dark circles around her eyes, she’ll shyly give it back to you. Maybe with the corners of certain pages turned down. Maybe with a flower or a card. The scent of cigarette smoke clinging to the pages.

Martin: I understand Iordana’s death freed you to publish the book. Did it also free the writing at all?

Colin: Yes. I realize we have much more in common. I can’t see a gull on our shore without thinking of the gulls on hers. Both of our boys are men now, on their own.

Martin: This is a story of late twentieth century Romania. Thirty years on, how universal is the tale? Do you see any special relevance to now?

Colin: Despots come in all packages. We have to be on the lookout for the scinteia, the sparkle of evil.

Martin: So a novel can make us better prepared for what is to come, by giving us a mirror from the past?

Colin: Past, present, and future. The easy way out is to say, “Did that really happen?” and “Is this really true?” “That must have been really different then.” Next up: “We wouldn’t do that. We would never be so clueless. We have social media; we’d never let that happen.” That’s a natural reaction we all have when we want to be let off the hook. A novel is timeless. The future is prologue.