“The Boston Castrato explores the beauty of the outcast.”

–The Virginian-Pilot

Order your copy today:

https://www.amazon.com/Boston-Castrato-Colin-W-Sargent/dp/1909954209/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1486570000&sr=8-1&keywords=The+Boston+Castrato

Music From 1922: “The Hoo-Doo Man.”

“A novel that captures 1920s Boston through the eye of a young Italian castrato seeking love.”

Awards:

First runner-up in General Fiction at the 2017 New England Book Festival

Honorable mention in General Fiction at the 2017 Paris Book Festival

Honorable mention in General Fiction at the 2017 Amsterdam Book FestivalX

Honorable mention in General Fiction at the 2017 San Francisco Book FestivalXX

Nominated for 2017 Library of Virginia Literary Award

London Review! https://morningstaronline.co.uk/a-59f0-hard-times-in-laboratory-of-nightmare-exploitation-1

Kirkus Reviews: https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/colin-w-sargent/the-boston-castrato/

Foreword Reviews: https://www.forewordreviews.com/reviews/the-boston-castrato/

Historical Novel Society: https://historicalnovelsociety.org/reviews/the-boston-castrato/

Maine Sunday Telegram: http://www.pressherald.com/2016/09/11/book-review-real-imagined-characters-make-memorable-music-in-the-boston-castrato/

The Virginian-Pilot: http://pilotonline.com/entertainment/arts/boston-castrato-explores-the-beauty-of-the-outcast/article_ca015406-96fe-5ea8-8eda-f9d2d6dd3f5d.html

Antic and episodic, The Boston Castrato is as hilarious as it is compassionate, intriguing and wise, the prose finely honed, and its metaphoric richness rendering even the darkest, zaniest scenes with a haunting tenderness. Colin Sargent is a fearless and generous writer, and his blend of humor and pathos takes the reader into both the heart of this story, and into the lives of these deeply imagined and unforgettable characters who inhabit it.’ –Jack Driscoll, author of The World of a Few Minutes Ago

https://morningstaronline.co.uk/a-59f0-hard-times-in-laboratory-of-nightmare-exploitation-1

Weaving together a dizzying number of intersecting plots, Sargent (Museum of Human Beings, 2009) captures the bustling excitement—and seedy grit—of early 1920s Boston.

As a child in Naples, angel-voiced orphan Rafaele Pèsca is taken under the wing of a renegade priest and castrated to protect his “one and only grace”—never mind that the practice is newly banned by the church. When higher-ups catch wind of what’s happened, Raffi is forbidden ever to sing again, at all, for any reason—his voice, having been “disfigured by the devil,” is now an abomination against God. And with that, the boy is put on a boat headed for an orphanage in New York City to “start a new life” not defined by “what is simply a medical condition.” But as adolescence approaches, his differences make him a target among the boys, and as his peers prepare to head to the front, Raffi hops on a boat back to Italy, where he excels on staff at the Hotel Forum, having discovered “a transforming eroticism in making strangers’ lives more fulfilled.” His return, though, is short-lived, and, rejected in Rome, Raffi once again heads toward America, this time to seek his fortune in Boston—ideally, at the world-famous Parker House, epicenter of the city’s elite. Arriving in the city, Raffi hustles his way into a job waiting tables and finds himself inducted into a society swirling with energy. Under the wing of Victor, his colleague and confidant, Raffi is introduced to the world of poet Amy Lowell and her partner, the actress Ada Russell, and their associates (many, though not all, of the characters here will ring a bell). He encounters love and tragedy, mobsters and mediums. While Raffi is the novel’s hero, the book is a whirlwind of perspectives and voices—some more successful than others—from art collector Belle Gardner to a colony of bacterium. The sheer number of characters can make the novel somewhat difficult to track, but the reward is a richly atmospheric melodrama that resonates.

Sweeping and ambitious.

Foreword Reviews

From its darkly picaresque beginning that features a cruel operation that alters a child’s destiny, Colin W. Sargent’s The Boston Castrato tells the strange and captivating tale of a rather different immigrant experience.

In 1906, little Rafaele Pesca, an orphan from Naples, is singing for his supper and loose change. He attracts the attention of Father Diletti, an unsavory priest who wants Rafaele’s voice to be even more distinctive—as a famed castrato. Though the procedure had been outlawed, Diletti performs the castration himself. Once the authorities learn what has happened, they take Rafaele away from Diletti’s clutches and urge the boy to start a new life. They also insist that he never sing again, because his voice is now “disfigured” by the devil.

Following an understandably confusing adolescence, Rafaele makes his way to Boston in 1922. Ambitiously charming, the tall, lanky Rafaele renames himself Raffi Peach and finds work at Boston’s Parker House Hotel. For anyone who might have imagined 1920s Boston to be a bit stuffy and not quite the toddling town of Chicago or New York, The Boston Castrato will likely change that opinion. Bustling with snobs, intellectuals, criminals, immigrants, artists, and a definite LGBT presence, Sargent’s Boston is vivid, violent, quirky, cultured, and peopled with memorable characters.

Raffi’s dreams of success in his adopted city are complicated by his desire to find a sexual identity. He pursues the lovely, compassionate Beatrice, but isn’t quite sure of what he has to offer romantically. Alternating with fictional personalities are characters like Imagist poet Amy Lowell and her longtime partner, actress Ada Russell. Initially suggested to be the “Yankee Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas,” Lowell and Russell share their own unique dynamic and are key players in The Boston Castrato’s plot.

Through personal triumphs and tragedies, Raffi’s support from Amy Lowell’s circle boosts his confidence and broadens his perspective, resulting in a lively American adventure that sparkles with wit and wisdom. –Meg Nola

Virginian Pilot

Author André Berthiaume once wrote, “We all wear masks, and the time comes when we cannot remove them without removing some of our own skin.” The latest novel from author, playwright and poet Colin W. Sargent, “The Boston Castrato,” grapples with the same crisis of identity through protagonist Rafaele Pèsca, Americanized as Raffi Peach, who himself laments, “So much of life was hidden behind the drapes of things.”

Sargent’s is a novel about the beauty of the outcast, and a critique of the perverse push and pull of society’s simultaneous exploitative fascination with and disgust for those who are different. Sargent, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, lives in Portsmouth and in Kennebunkport, Maine, and his time spent stationed in Naples is reflected in his crafting of a novel about an Italian immigrant in America.

Raffi lives on the streets of Naples until he is 6, when a priest, Father Diletti, persuades him to join his choir. Diletti violates the church’s ban and castrates Raffi so that he may grow to be the next great castrato singer, like Alessandro Moreschi. Upon discovering this violation of its rules, the church sends Raffi to America to get him out of Italy. Before he leaves, the church makes Raffi swear that he will never sing again, leading to a lifelong internal struggle between his desire to celebrate his gift and to hide it out of shame.

After he travels between Italy and America for years off the page, we pick up with Raffi, abnormally tall with an androgynous voice and appearance, returning to Boston in 1922, 16 years after that fateful day in Italy. In Boston, he finally begins to reckon with himself and his past. His struggle with his identity, his desire to make something of himself, and his search for someone who will love and accept him are set against a backdrop colored with the brightest and darkest parts of 1920s Boston.

Raffi’s journey touches the most elite parts of Boston and sinks to dangerous depths as he works at a variety of places, from the famous Parker House hotel to communing with the dead for the Boston Society for Psychical Research. His zigzagging odyssey includes a rival from his past, the Italian mob, and has him grappling with the loss of loved ones. Although Raffi initially feels alone with his secret, he meets friends in both similar and vastly different situations and explores his identity. As he seeks the freedom to feel comfortable inside his own body, he also questions the consequences, as when he and his new friends cross-dress for the night:

A sunny freedom sailed over him. He’d never been so far outside himself. He was accustomed to women’s eyes being on him, either out of curiosity or pity, and to unsettling glances from lonely blades, but here were gentlemen’s eyes, too. Passing to the ballroom, he caught a glimpse of himself in a gold-veined mirror – nightmarish lipstick, eyeliner, rouge, and all. “You look very becoming,” the reflection said to him. “But what are you becoming?”

Through this journey, Raffi becomes increasingly focused on an upcoming performance by his idol, the castrato Moreschi. In all of his suffering, Raffi finds solace in knowing that Moreschi has gone through the same and come out thriving. However, Raffi, always observing and questioning himself as well as those around him, begins to doubt his own belief that Moreschi will hold all the answers he needs.

For weeks, he’d wondered about his need to talk with Moreschi and decided it was because Moreschi had plunged on ahead of him – an explorer on an expedition of hurt. Maybe culture, and particularly embarrassment, had a line of descent, too.

One of the book’s most admirable accomplishments is the sheer range of characters and its commitment to showcasing a wide variety of self-defined outcasts, whether due to gender, age or physical impairment, and how they embrace their differences.

Sargent’s critique of 1920s society resonates today, calling for understanding and acceptance in the face of anything considered less than normal. In its colorful illustration of 1920s Boston, impressively showcasing Sargent’s extensive knowledge of both castrati and 1920s Boston culture and his carefully constructed prose, the story at times veers a little far into the bizarre, such as in a section told from the point of view of bacteria encased in canned clams. However, ultimately, Raffi’s multifaceted journey celebrates the strange and proves an endlessly entertaining ride through his world and the challenges he faces. From revenge, murder, lifelong rivalry, and love, little cannot be found in Sargent’s “The Boston Castrato.”

Editor’s Choice: Historical Novel Society

At the turn of the 20th century in Naples, the Catholic Church is trying to remove some of its older, darker habits, but one bishop still clings to tradition and castrates Raffi, a street urchin with a beautiful voice. Hastily covering the scandal, the church transports Raffi to America, where he is forbidden to sing and trains as a hotel concierge. Transported into the world of the literary glitterati of 1920s Boston and with the aid of a blind friend, Victor, Raffi makes his way through life.

In this new and vibrant but often harsh world, Raffi meets a host of characters, both famous and infamous, many of them misfits struggling to be accepted. Refusing to be defined by his secret, Raffi infiltrates the lives of the poet Amy Lowell and her friends and hangers on and becomes enmeshed in this strange, rich and sometimes criminal world.

Beautifully written, by turns poignant, sad and funny, this novel explores many themes, particularly those of prejudice and marginalisation. The transgender issues particularly are topical today. As a reader I wished I had better knowledge of the literary and political issues of the time and, indeed American readers might find this easier. Mixing fact and fiction, Raffi’s search for love and acceptance is both heroic and touching. His character is strong and defies pity and the ending of the book is genuinely uplifting. Colin Sargent’s use of language betrays the fact that he is also a poet, and descriptions are both memorable and entertaining. An enjoyable read, but I found that the unusual small font of this edition – Goudy Modern – made concentration a little difficult; it might be easier on an e-reader.

–Maggi de Rozario

Maine Sunday Telegram

Book review: Real, imagined characters make memorable music in ‘Boston Castrato’

Colin W. Sargent’s 1920s novel hits all the right notes on accuracy and fervor.

“The Boston Castrato.” By Colin W. Sargent. Barbican Press. Paperback. 292 pages. $17.95.

What a dream! What a song! Portland author Colin W. Sargent’s second novel, “The Boston Castrato,” is a whirlwind tale, abounding in fully realized historical and imagined characters, with convincing yet phantasmagoric settings that suggest a mild hallucinogen. Storylines appear to veer in all directions, but never fear, there is a core trajectory.

Shot through with wordplay that a few readers might term cruel and unusual punishment, the book is a nonstop delight to read. In spite of what the title might seem to suggest, it proves a love story.

This is the epic story of one Raffi Pesca, a Naples street urchin taken in by a creepy but earnest talent scout of a priest in 1906. The price of this ecclesiastical largesse is Raffi’s manhood. The reward: some gold coins and the gift of an extraordinary singing voice. However, high church officials, in a fit of early-20th century political correctness, defrock the priest, close his operation down and inform him that the “church is no longer in the monster business.” As with so many situations Raffi will soon encounter, this is the twilight of a tradition.

Not knowing quite what to do with the maimed child, church fathers rename him Rafaele Peach, give him a ticket to America, a start in the new world in a Bronx orphanage smack in the shadow of a neon sign for Underwood deviled ham. That sign, ubiquitous in the Northeast, will play a role over time and place, as both symbol and physical prop.

Adventures move our hero to Boston, Italy and back to the Yankee hub of the universe in the early 1920s, where a bewildering series of events ensnares and informs the now half-worldly, half-naïve but ever-ripening Peach.

At its widest scope, “The Boston Castrato,” is a first-rate picaresque, which should be read for the pure pleasure of the story, characters and ambiance. There are more circles than “The Divine Comedy,” as Sargent weaves together an investigation of the sterilization and sealing of “bad clams,” the unfolding of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial and Ezra Pound’s savaging of poet Amy Lowell’s imagism as “amygism.”

Truly, though, it is Sargent’s impressive knowledge of place, time, people and spirit that sets the novel spinning on its own internal axis. Indeed, the author states that his insight into Naples was largely gained during his hitch in the Navy as a helicopter pilot and, though the story only resides there briefly, it is most convincing. The reader is bound to ask where Sargent gained such a wondrous, convincing understanding of the Boston literary, cultural and criminal life in the 1920s.

As a great fan of that time and place, then in its gaudy twilight, this reviewer stands in awe of the historical assuredness of place and character-driven pace. Much of the action surges in and around the grand Parker House, a surviving icon.

As the blare of the 1913 Armory Show and Jazz Age swamp the bohemian Brahmins and their minions, and as gifted amateurs are overtaken by professionals, one enters a fantastic world not available in a Frommer’s Guide list of worthies, available nowhere else that I am aware of, at least not in such honesty and resplendence. The characters may all wear masks, but in the end they reveal parts of themselves in sober honesty.

In the end too, Boston Brahmin poet Amy Lowell and her presumed literary executioner both lie entombed in the same academic encyclopedias, each given their own devil’s due. As for Mr. Peach, he takes his place among literature’s delightful and original characters.

–William David Barry

Washington City Paper

https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/arts/books/blog/20848350/the-boston-castrato-reviewed

By Eve Ottenberg

Mutilation is not an easy fictional theme, especially when a story opens with the castration of a six-year-old. This brutal, gory start is referenced repeatedly in Virginia-based author Colin Sargent’s new novel, The Boston Castrato, and it is not the only mutilation explored; foot binding is referred to, as are the podiatric agonies of ballet dancers. “It was every dancer’s secret shame. Each of her toes was bunged and purple with blood and coagulant, pus oozing from her split and ingrown nails.”

The idea, clearly, is the physical suffering endured for art; but the novel extends it to include the social and emotional contortions associated with music, dance, and poetry. With this theme, the novel sometimes succeeds and sometimes does not. When it does not, though, it is usually because a graphic description is deployed when a simple, realistic one would work much better. And realism does not require that every gaudily gruesome detail be exposed, merely that a social world that could exist, that may exist, be evoked.

The best sections of The Boston Castrato recount with easy realism the hero’s work in a hotel, another character at work in a shipyard, and other such seemingly mundane activities. The novel vividly renders the hotel—the Parker House—from the subterranean dish-washing stations to the gleaming wood of the bar, to the perfectly appointed dining room, to the owner’s office, and more. Indeed, the Parker House is more than mere setting, it is practically another full-fledged character, largely due to its pellucid rendering as a social milieu.

Then there are the literati and other luminaries. Since the book is a period piece, set in 1920s Boston, that era’s famous people—the art patroness Isabella Gardener, John Singer Sargent, and, from Vienna, Anna Freud—make appearances, while numerous others are mentioned: Sacco and Vanzetti, Henry James, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Bernard Berenson, and D.H. Lawrence. There are also allusions to the Russian revolution and the vogue of imagist poetry, which give the novel pizzazz, while the plot and subplots provide substance. But at the center of The Boston Castrato is the hero Raffi’s mutilation, which throws a terrible obstacle in the narrative’s path, namely the reader’s pity for him.

At one point Raffi gazes into the eyes of a circus freak: “Dare you come into my loneliness?” is what he sees. This has nothing in common with some happy, 21st century tale of transgender redemption through surgery. Raffi was swindled out of his manhood and repeated mention of the bloody act impedes appreciation of who he becomes.

The Boston Castrato’s real strengths lie not in evoking a bygone era or the physical torments endured for art, but in its characterization and how it weaves together subplots. Raffi’s friend and boss at the hotel, a blind African American named Victor, is in many ways the book’s central concern. A subplot involving an Italian immigrant family and a communist Harvard student who travelled to Soviet Russia somehow holds your attention better than the details of cross-dressing and catty infighting in the upper crust, blue-blood, gay precincts of ragtime Boston.

There are also strong portrayals of crooked pols, hit men, imposters, gangsters, aspiring singers, and psychics—pictures that advance the plot and subplots—which don’t really pick up steam until halfway through the book. But when they do, they barrel on to their dramatic conclusions, finally pulling the reader past that crippling pity for Raffi to an appreciation of this novel’s achievements.

Author Reviews

I am really enjoying reading The Boston Castrato. The novel gives me a sense of the twenties much like The Great Gatsby does, but in more depth and … well, an intimacy … I feel present in the time period, and largely in completely unexpected ways … such as “night-blooming hierophant” — LOL. So many of the 20s’ “enthusiasms” are caught in your book in delightful fashion, and these diverse delvings create a rich fabric of time and place. The people. The characters. Amy Lowell and her gang are brilliant–and much fun to follow. The bizarre (for us moderns) interplay between the classes and license given to the wealthy is again reminiscent of Gatsby, which is–at its heart–about class. Many of the same brutal realities of the time we see in Gatsby’s New York appear in Raffi’s Boston, but with a brighter light cast on them, and seen from up close. I really like the Italian sayings at the start of each chapter. And the gender issues? Like many today, I sometimes think of the 20s as ancient–and dry … but you bring to life the advanced ideas and daring lifestyles that people were experimenting with.

–Jennifer Hegeman

I hadn’t yet read The Sun Also Rises, but when I recently got round to doing so, after meaning to for many years, the restless way the characters all ceaselessly strive to out-snark each other reminded me of The Boston Castrato.

–Gwen Thompson, author, Men Beware Women

AMY LOWELL MAKES A NOVEL APPEARANCE

AMY LOWELL MAKES A NOVEL APPEARANCE

From Barbican Press: “We have a classy novel coming out this spring. The Boston Castrato by Colin Sargent contains many themes and wonderful characters, and is a striking introduction to many facets of Boston life in the 1920s. Paramount among those is the poet Amy Lowell, who had skipped our attention till now. Amy and her companion Ada Russell might have outmuscled Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in a wrestling ring and were very much of that ilk. Perhaps it was their staying in the family’s baronial pile in Boston that kept their reputation more local, while Gertrude and Alice queened it in Paris. Hopefully this new novel will boost the Bostonians’ reputation a little.

“Here’s how Chapter 11 introduces the pair, our principle protagonist Raffi climbing the stairs of their home:”

‘Raffi followed Victor up two landings to the third floor. Victor put his finger to his lips as they stood in the open doorway of an immense room lined with nail-studded leather Chesterfields.

‘At the bar, three sleepy-eyed gentlemen nursed drinks beside two gamine ingénues. Amid the murmur, cat slept on an ebony piano, sun-faded to a pearly gray. Center stage, on an overstuffed tapestry couch, their hostess lounged in silken trousers, puffing on an Ilusione cigar. Beside her Ada Russell sat stiffly, her face as well as arms crossed, her forked cane leaning against her chair.’

And here is the newly minted poem Amy Lowell goes on to recite:

You are beautiful and faded Like an old opera tune Played upon a harpsichord; Or like the sun-flooded silks Of an eighteenth-century boudoir. In your eyes Smoulder the fallen roses of out-lived minutes, And the perfume of your soul Is vague and suffusing, With the pungence of sealed spice-jars. Your half-tones delight me, And I grow mad with gazing At your blent colours.

My vigour is a new-minted penny, Which I cast at your feet. Gather it up from the dust, That its sparkle may amuse you.

‘We look forward to bringing Amy and Ada to you in The Boston Castrato in March, full-bodied and alive and in great company.’

WHY AMY LOWELL?

WHY AMY LOWELL?

Amy needs no spirited defense. She’s earned a spirited understanding. Her time has come. Jilted for her sex, her sexuality, her excess, her age, her means, her patriotism, her cigar smoking, her sartorial choices, her Boston provincialism, and her family, Amy Lowell had the guts to steam on and develop her talent. Growing up in Brookline, Massachusetts, she had to fight being invisible even at her own dinner table at Sevenels (named for seven Lowells). One brother was president of Harvard, who hunted down and persecuted homosexual undergrads. Another brother was the renowned astronomer who discovered Pluto. Who was watching the pale younger sister? Undercut by cosmic loneliness, Amy would challenge her limits until she became a sensational human being, crying for justice from the grave.

After decades of neglect, a timely awakening of appreciation of her talent is afoot. Though she was granted a posthumous Pulitzer in 1926 for What’s O’clock, she was ignored for nearly a century and dismissed, even occasionally by her own biographer. An informal tally of 1975’s Amy: The World of Amy Lowell and the Imagist Movement reveals she’s referred to as “fat” dozens, if not hundreds, of times in the text. Universally, there’s been an unexplored sense of how dare this rich little rich girl ever try to understand and interpret the world, especially if she’s earned the Scarlet F? Her successor in the Lowell family, the Boston poet Robert Lowell, once let slip that he considered his aunt Amy “big and a scandal, like having Mae West in the family.” Daringly, she also wore the Scarlet L.

Loud Amy traveled the world with her maroon Pierce-Arrow shipped shore-to-shore, engaging the most luxurious suites and always accompanied by the lovely actress Ada Russell. There weren’t just whispers, there were outright jibes and how-dare-she’s: “Who is this Yankee, and what gives her the right to flaunt her lover here?” Amy materializes as a singular character: vital, juicy, and courageous. Inspired by the Imagist revolution and restless with her traditional poetic style, she dropped her life in Boston and risked everything in 1913. She was off to London to study with the much-younger Ezra Pound and share ideas with emerging literati. The Imagists were a fast crowd, ascerbic and D.H. Lawrence-cool. Would they see beyond her checkbook? Amy feared her fortune would keep many critics from taking her seriously, and the Imagists from accepting her as one of their own. She suspected her wealth was creating a glass floor for her. The showdown came at an infamous dinner party at the hotel Dieudonne, Ryder Street, St. James’s, London, with some of the hottest writers in the world in attendance: Lawrence; Richard Aldington and his wife, H.D.; F. S. Flint; John Gould Fletcher; Allen Upward; John Cournos; and the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzesca. Ezra Pound attacked; Amy had just refused him a loan for artistic projects. Making use of props from the dining hall, Pound savaged “In A Garden,” the very poem he’d just published, which stars Ada bathing in moonlight. Uncomfortable, the other guests were forced to take sides. A clatter of cutlery. Merlot splashed in pique. The stuff of one-act plays. It is impossible to study the Imagists in the U.S. without studying Amy Lowell. Her role as an opposition character to Ezra Pound injected incredible energy to the Imagists. Locked in a death struggle with him forever, she is Pound’s Other. Her poems to Ada, so violently maligned, are some of the most touching words ever written.

Loud Amy traveled the world with her maroon Pierce-Arrow shipped shore-to-shore, engaging the most luxurious suites and always accompanied by the lovely actress Ada Russell. There weren’t just whispers, there were outright jibes and how-dare-she’s: “Who is this Yankee, and what gives her the right to flaunt her lover here?” Amy materializes as a singular character: vital, juicy, and courageous. Inspired by the Imagist revolution and restless with her traditional poetic style, she dropped her life in Boston and risked everything in 1913. She was off to London to study with the much-younger Ezra Pound and share ideas with emerging literati. The Imagists were a fast crowd, ascerbic and D.H. Lawrence-cool. Would they see beyond her checkbook? Amy feared her fortune would keep many critics from taking her seriously, and the Imagists from accepting her as one of their own. She suspected her wealth was creating a glass floor for her. The showdown came at an infamous dinner party at the hotel Dieudonne, Ryder Street, St. James’s, London, with some of the hottest writers in the world in attendance: Lawrence; Richard Aldington and his wife, H.D.; F. S. Flint; John Gould Fletcher; Allen Upward; John Cournos; and the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzesca. Ezra Pound attacked; Amy had just refused him a loan for artistic projects. Making use of props from the dining hall, Pound savaged “In A Garden,” the very poem he’d just published, which stars Ada bathing in moonlight. Uncomfortable, the other guests were forced to take sides. A clatter of cutlery. Merlot splashed in pique. The stuff of one-act plays. It is impossible to study the Imagists in the U.S. without studying Amy Lowell. Her role as an opposition character to Ezra Pound injected incredible energy to the Imagists. Locked in a death struggle with him forever, she is Pound’s Other. Her poems to Ada, so violently maligned, are some of the most touching words ever written.

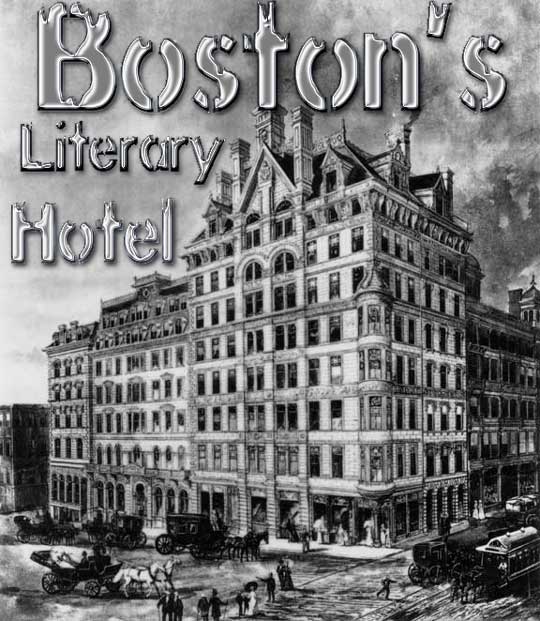

Experience 1920s Boston and the Parker House

Nicknamed America’s Literary Hotel, the Parker House, est. 1855, is the oldest continuously operating resting place for travelers in the United States, as Raffi brags to mysterious Beatrice during their date on the Common (“So it’s a cemetery,” she replies). Charles Dickens kept a suite of rooms here during his extended American tour. Because the Saturday Club met here, the Parker House was the weekly home to Longfellow, Emerson, Agassiz, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. Dreamers with all manner of industry have crossed paths at the hub of The Hub, both upstairs and downstairs. In 1912, Ho Chi Minh baked the famous, fragrant Parker House rolls in the lower depths of the hospitality world, where blind Victor reigns. During World War II, Malcolm X served as a waiter.

It is also put forth that the Parker House introduced the world to Boston Cream Pie and scrod, and brought warmth, elegance, and romance to cold Beantown. Senator John F. Kennedy proposed to Jackie Bouvier in the hotel dining room. More than 60 years later, the maitre d’ still smiles when Table 40 is requested.